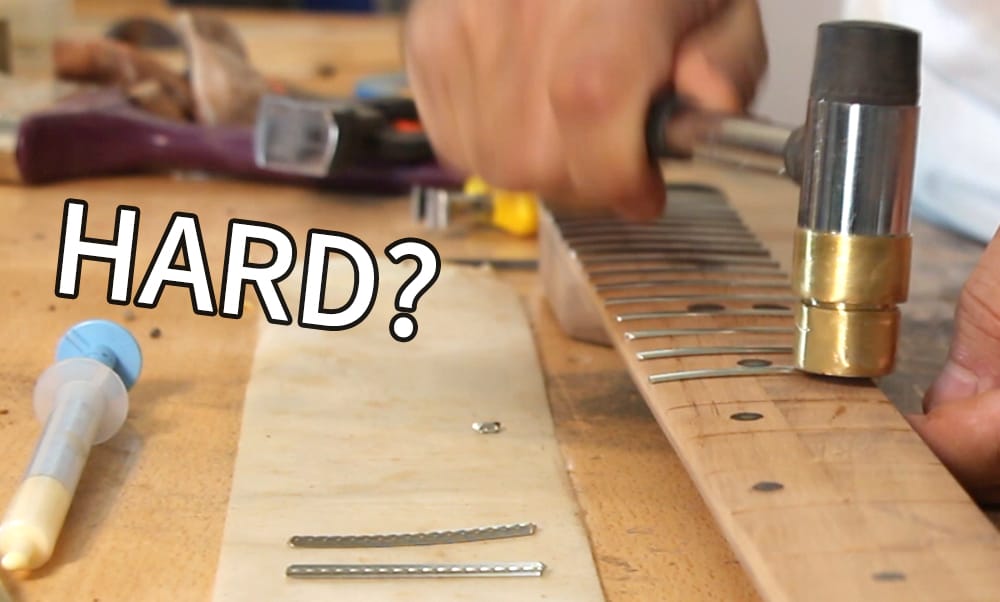

Building a simple electric guitar is not particularly hard, but it is complex and requires a few, very different skills and quite a few tools, including some specialty tools. Building a high- end guitar however, is very hard and will require a high level of skill in more than area. We also need to be very clear about what we define as ‘building a guitar’ as there are a few very different routes to take which will all lead to a guitar but with great differences in time, budget and difficulty. These will include ‘Kit Guitars’, assembling a ‘Parts Guitar’ and ‘Building from Scratch’.

How to dry wood for guitar building?

The general consensus is that you want the wood to reach the moisture content of the environment it is in. In most modern homes this would mean 6-9%. The main advantage of wood with this moisture content is that it will not deform or change shape when the instrument is built.

To better understand the process and principles of drying the wood we’ll take a deep dive into kilns, de-humidifiers, and humidity.

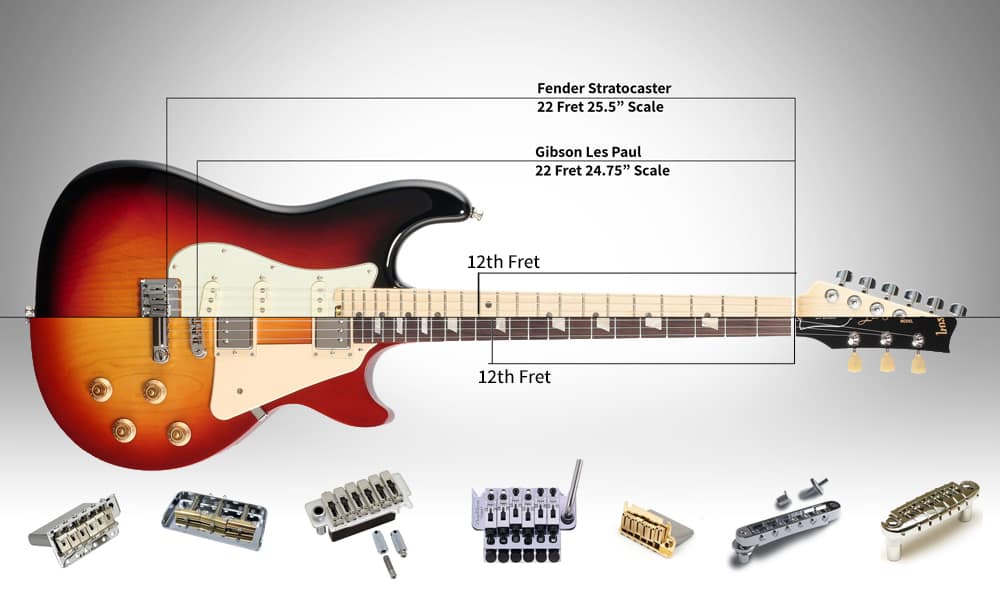

How to Determine Guitar Bridge Placement on any Guitar

On pretty much every guitar the bridge should be located so that the break point of the string will be exactly at the distance of the scale length, from the nut. The scale length of any guitar is defined as double the distance from the nut to the 12th fret.

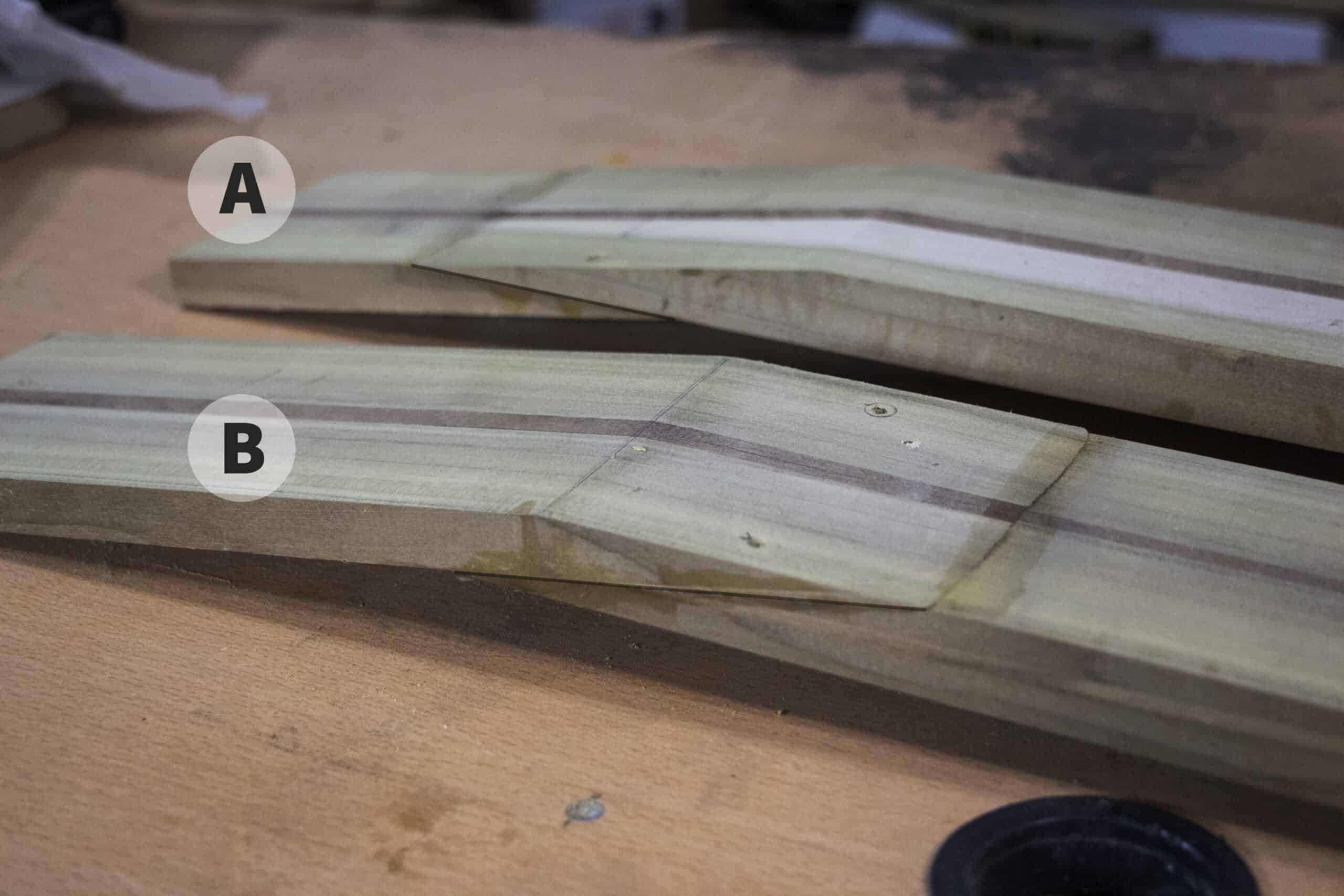

What is a Scarf Joint on Guitars and How to Cut and Glue It?

The scarf joint is a method of connecting a separate piece to create the tilted headstock in a way that eliminates the point of weakness that is created when building it from a single piece of lumber. There are two common methods to achieve this and they involve cutting the headstock part at the desired angle, flipping it, and re-gluing in an angle. More on how to do it in a bit.

How to Paint and Finish a DIY Guitar, with No Special Tools

There are generally three ways (with different difficulty levels) you can finish your guitar, to look great, without investing in expensive equipment, fancy polishing and buffing wheels, or a painting booth.

• Applying an oil finish (with or without staining)

• A Mat finish over solid colors or stains

• High gloss finish over solid colors

These will require no cost other than the materials themselves, maybe some brushes, thinners if needed and sandpaper of different grits.

Are DIY Guitar Kits Worth It? The Pros and Cons of Kits

The premises of a guitar kit seem very appealing to DIY enthusiasts, many guitar players and couples of the above thinking of a present. For some, this may be a stepping stone to building more guitars or maybe even a ‘scratch build’, and for others, it’s a one-time project. There are multiple websites dedicated to […]